Some people have a drive in them to prove others wrong and to do what no one else has done. Nellie Bly was one of those people.

Born in May 5 1864, with the name Elizabeth Jane Cochran, using Nellie Bly as a pen name, she became one of the first modern investigative journalists, decades before the height of the muckrakers.

Bly got her first job at the Pittsburgh Dispatch, in 1885, by writing an angry letter to the paper in response to an article titled "What Girls Are Good For" and worked there as a reporter for about two years on the women's pages. This was also where she decided to use a pen name, choosing "Nelly Bly" originally, but after a mistake by her editor writing "Nellie" she stuck with the new one.

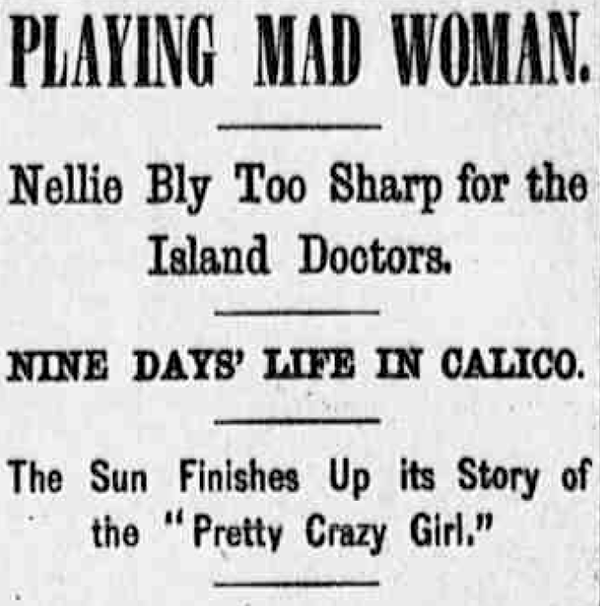

Leaving for New York in 1887, Bly got a job at Joseph Pulitzer's New York World, where she wrote the most important piece of her career. Going undercover at Blackwell Island's Women's Lunatic Asylum for 10 days. She published 6 gruesome exposes on the inhumane treatment and conditions, bringing justice to the patients and revolutionizing medical care in the United States. Writing two books, 10 Days in a Mad-House and Behind Asylum Bars.

From 1886 to 1887, Bly traveled to Mexico to report on the corruption and condition of the poor, until she was deported because of her writing. In 1888, she decided to make Around the World in 80 Days a reality. Departing from New Jersey, only 72 days later she returned, completing most of her journey alone. Bly held the record only for a few months, as her record was beaten by five days.

Bly married a steel manufacturing company founder, and when he died in March of 1904, she took over the company. Taking a break from writing, Bly ran the Iron Clad Manufacturing Company until it went bankrupt. In her tenure, she patented multiple inventions including, the 55 gallon oil drum that is still in use today, and the stacking garbage can. The company went under after Bly prioritized the workers and their conditions and they took advantage of her, embezzling money from the company until there was nothing left.

Returning to writing, Bly went to work for Hearst's New York Evening Journal, where she covered the women's suffrage movement. She was also the first woman and first reporter to see the Eastern Front of Serbia and Austria in WWI.

Nellie Bly, legally known as Elizabeth Cochran Seaman, died Jan 27, 1922, doing what she was best at, writing.